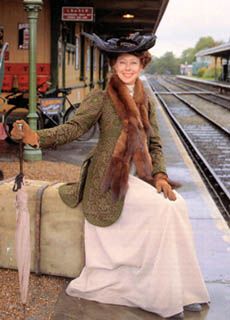

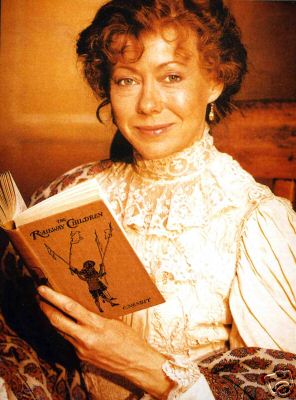

In 2000, Jenny made her third appearance in Edith Nesbit’s much loved The Railway Children – this time as Mother.

Jenny on Playing Mother in the Carlton TV production of The Railway Children.

OTHER PEOPLE, it seems, are disconcerted by the idea of my playing Mother. Holding on to their memories of Lionel Jeffries’s 1970 film of The Railway Children, in which I played the oldest child, they ask: are we going to have to confront a grown-up Roberta? Does this mean that our view of Roberta is under threat?

I have lived the 30 years in between, so I don’t have any confronting to do. The person that I was in 1970 is still there within me, but three decades have passed. The story remains the same, but the world has changed since it was last told. Other people will have to come to terms with their own 30 years of growing up.

Part of my preparation for the new film was to look for aspects of the story’s author, Edith Nesbit, in the character of the mother. As a result, I imagined someone much less capable than was portrayed by Dinah Sheridan in 1970. She created – brilliantly – a child’s view of a perfect mother, which fitted snugly into the world Lionel Jeffries was evoking. By contrast, Nesbit’s life was always unstable. What saved her was her belief that things would work out in the end.

Nesbit’s life shows us a woman who respects the rules of society. But she can’t live by them, because it doesn’t work for her. The values of marriage are terribly important to her, but her desire for freedom and independence means that she does not want to be bound by duty to her family. She was not a perfect mother

You could say that her husband’s infidelities created difficulties for her, or that they created the separation she needed. At the same time, he was the one person she wanted to be with. Against the background of her own tense and complex family life, she wrote stories about families that knitted perfectly together.

In something of the same way, the first film of The Railway Children defied the tensions of its time. It was made as we emerged from the 1960s. Rock music, student revolt, the Pill, Vietnam – where did this film about innocence, beauty and security fit into all that? Yet it obviously made a deep impression.

What background does the new film stand against? It was shot in the autumn and has a more frail feeling, a sense of hanging on to each moment without knowing what the future will hold. Nesbit, like many writers of her time, believed that a socialist Utopia was genuinely about to dawn. She looked forward to a society so perfect that people could not fail to be good within it. Yet between her life and ours, two world wars have taken place. We have had it shoved down our throat that we will never see heaven on Earth. We have grown up.

Yet I believe there is still a place for innocence, and that we can seek it in ourselves as adults as well as cherishing it in children. Perhaps this is what Nesbit was exploring in her writing. The mother in The Railway Children writes stories for children in order to earn money, just as Nesbit had to do. Is the story she is writing The Railway Children? Although the book is told in the third person, she seems at times to inhabit the mind of Roberta, her child. The descriptions, too, are filled with childlike wonder.

The parallels with my two roles in the two films are, for me, inescapable. In certain respects, Nesbit was writing not about her children but her own childhood. It was when she was a child in Kent that she lived near a railway line. Roberta waves a red petticoat to stop the train. Red petticoats were worn in the 1870s, when Nesbit was a child, not in 1905 when she wrote the book.

The child who played Roberta in 1970 is now a mother. Many of the questions that now occupy my mind are about growing up: about what my parents have given me, about what I can give to my son. They are questions I could not have asked as a child.

For many of us the loss of innocence is painful to contemplate. But if we find that magic can come in a new way, that the world contains even more to wonder at than we could have imagined as children – than there is hope that we can keep hold of our childhood, use it well, and once again begin exploring.